Why don't digital creations feel like my own?

As digital creation tools become faster and more automated, creative efficiency increases, but we lose authorship consciousness and sense of ownership. According to prior research, automation tends to hide visible effort and weaken psychological ownership without improving idea quality.

Seoul-based creative coding club, TypeLab

Graphics made with digital tools feel like code files floating on a screen. They're just temporarily rendered images, and they don't really feel like mine.

Member JangMore like a code file floating on a screen, a momentary rendering that I don't truly hold or own.

Member LeeAll I did was write a few prompts, so I wondered if I could even call this my work.

Member KimWe shared a recurring feeling that code art can seem distant. We started asking what kind of materiality code art can have, and what realistic ways there are to distribute it. I wanted to unpack the questions we raised together that day.

How AI Automation Affects Creative Ownership and Idea Quality

To explore the problem space more deeply, I conducted desk research to gather actionable insights. The research revealed that as digital creative tools become faster and more automated, creators experience increased efficiency—but at the cost of authorship and ownership. Prior studies show that automation often hides the visible effort behind creative work, weakening psychological ownership without actually improving the quality of ideas.

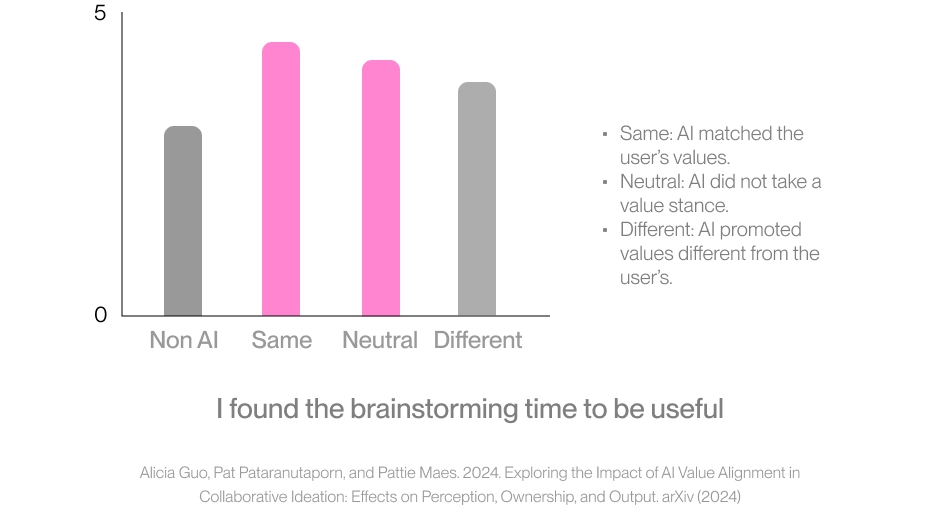

1. Brainstorming feels more effective with conversational AI

Participants were able to explore ideas more quickly through iterative conversations with AI and responded that it was more helpful in the brainstorming process.

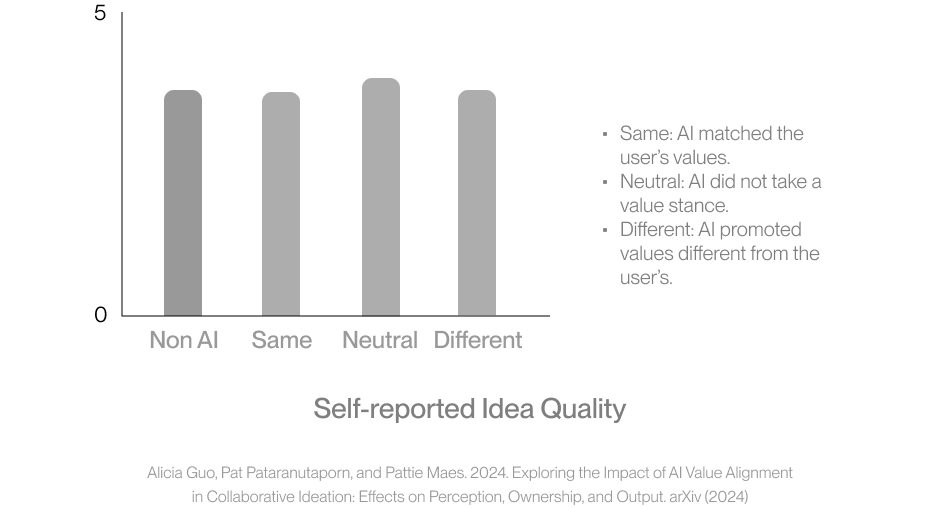

2. Idea quality did not significantly differ

Creators reported that there was no significant difference in idea quality between conditions with and without AI use.

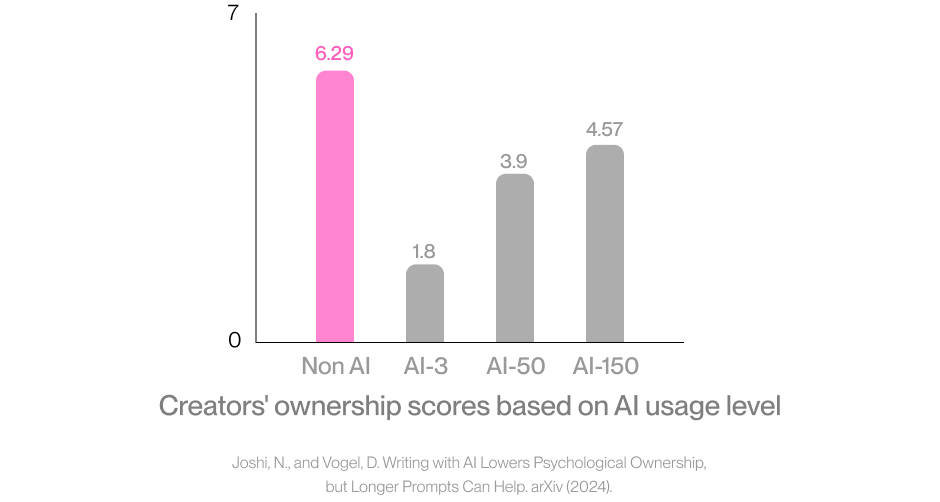

3. Automation reduces authorship and ownership

When measuring sense of ownership over creations on a 1-7 scale, as AI involvement increased, the sense of ownership felt by creators dropped sharply.

Key Insight

Automated tools increase efficiency and convenience, but they don't elevate the quality of ideas. Rather, creators often lose their sense of ownership in this process. Therefore, when designing automated tools, it's important to design interactions that allow creators to actively engage and perceive their own effort.

Where does the sense of ownership over creations come from?

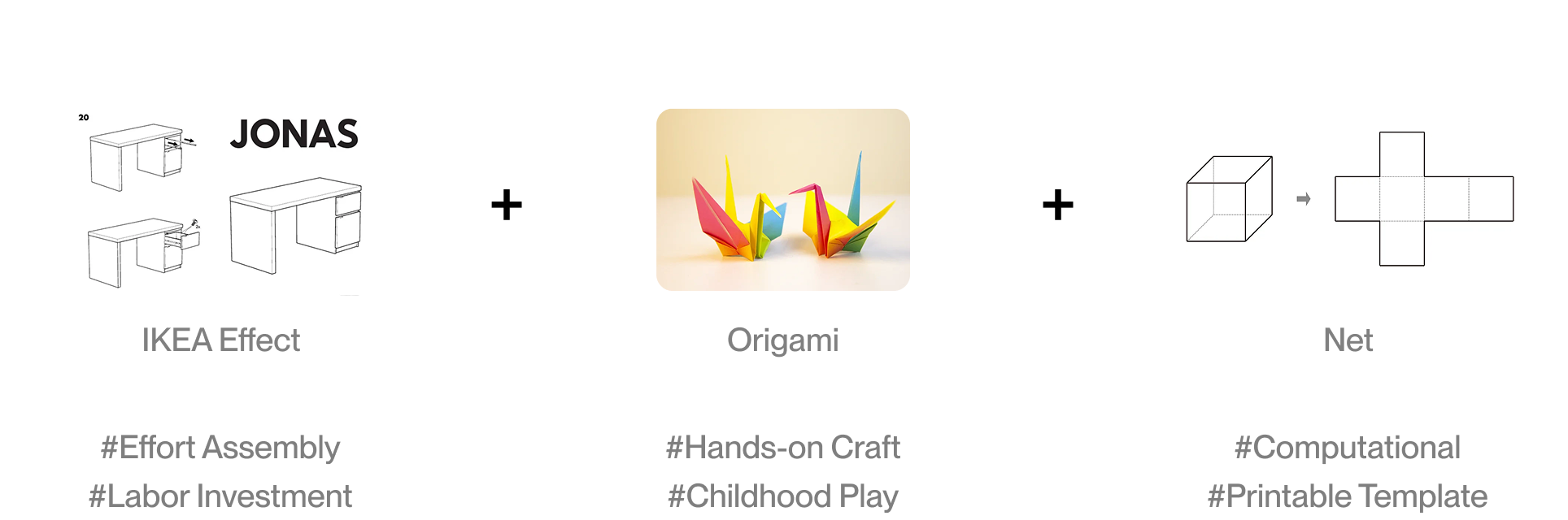

According to the IKEA effect, people assign higher value to outcomes they've personally invested effort in and feel a stronger sense of ownership. Noting that automation increases efficiency but weakens ownership, I sought to apply the IKEA effect to creative coding tools.

What creates ownership?

Effort and time | People value creations more when they've invested significant effort and time into making them.

Design implication

Sense of ownership emerges when the process of effort, judgment, and revision is visible. This suggests that automation should not replace the act of making, but rather assist in the process of making.

Transforming digital creation into a hands-on experience

Based on insights from desk research and direct observation of creative coding classes, I reframed my approach to digital making. Instead of one-click automatic generation, I shifted toward a construction-based approach where students put in effort and assemble things themselves.

Key Question

Reframing digital making through effort and assembly

"How can we provide the convenience of automation while not losing the sense of having made it yourself?"

One of the representative creative coding platform, p5.js editor

Ideation Leap

From Generation to Assembly

Shifting digital creation toward hands-on construction

Inspired by the IKEA effect, origami, and paper craft templates, I designed a tool that allows users to create digital outputs through hands-on experience.

Designing for ownership in TypoFold

Based on the research, I established three design principles for TypoFold.

Make structure visible

Provide paper craft templates that can be assembled by hand, instead of finished products.

Rather than hiding the generation process, I made it so users can directly see and manipulate how forms are created.

Design for meaningful effort

Sense of ownership comes not from the result, but from the process of making.

I designed an experience where users make things themselves through folding, assembling, and choosing, rather than simply receiving the final product.

Supportive

Automation doesn't mean making it for you; it means enabling you to make it yourself.

Automation is used to generate structures that users can transform, combine, and modify.

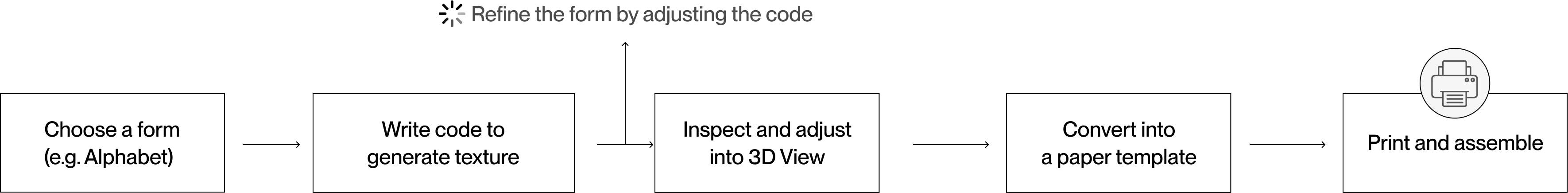

Creating a pipeline to generate paper craft templates from 3D models

I chose the alphabet as the first application case. Letters can form various words, and each one functions as a module. Additionally, they can accommodate various languages and typefaces, offering a wide range of variations. Based on this first case, I plan to expand to 3D models beyond the alphabet in the future.

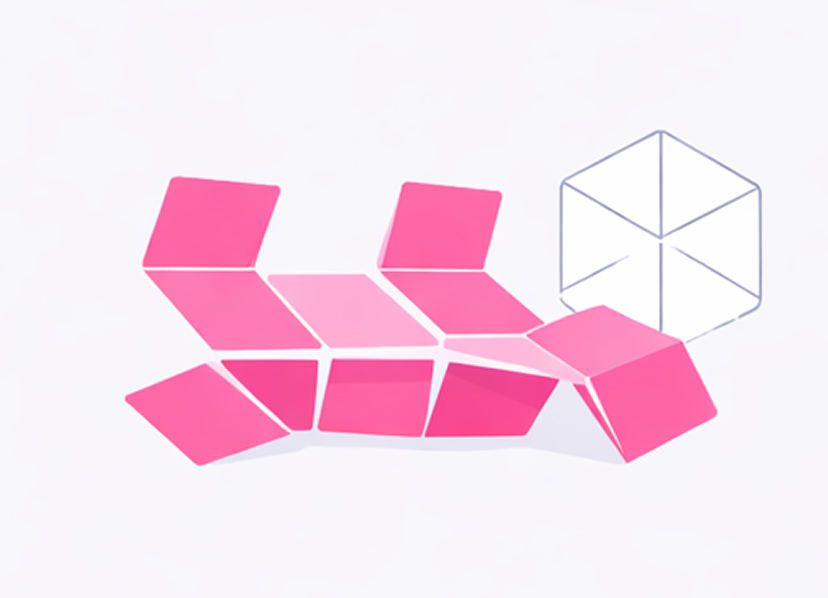

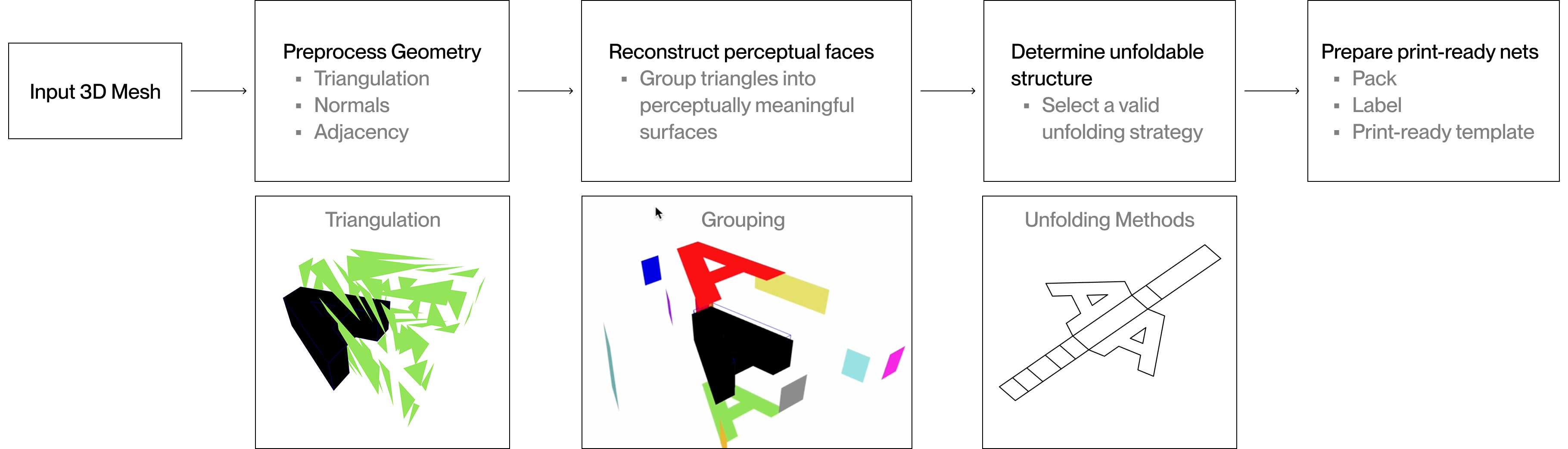

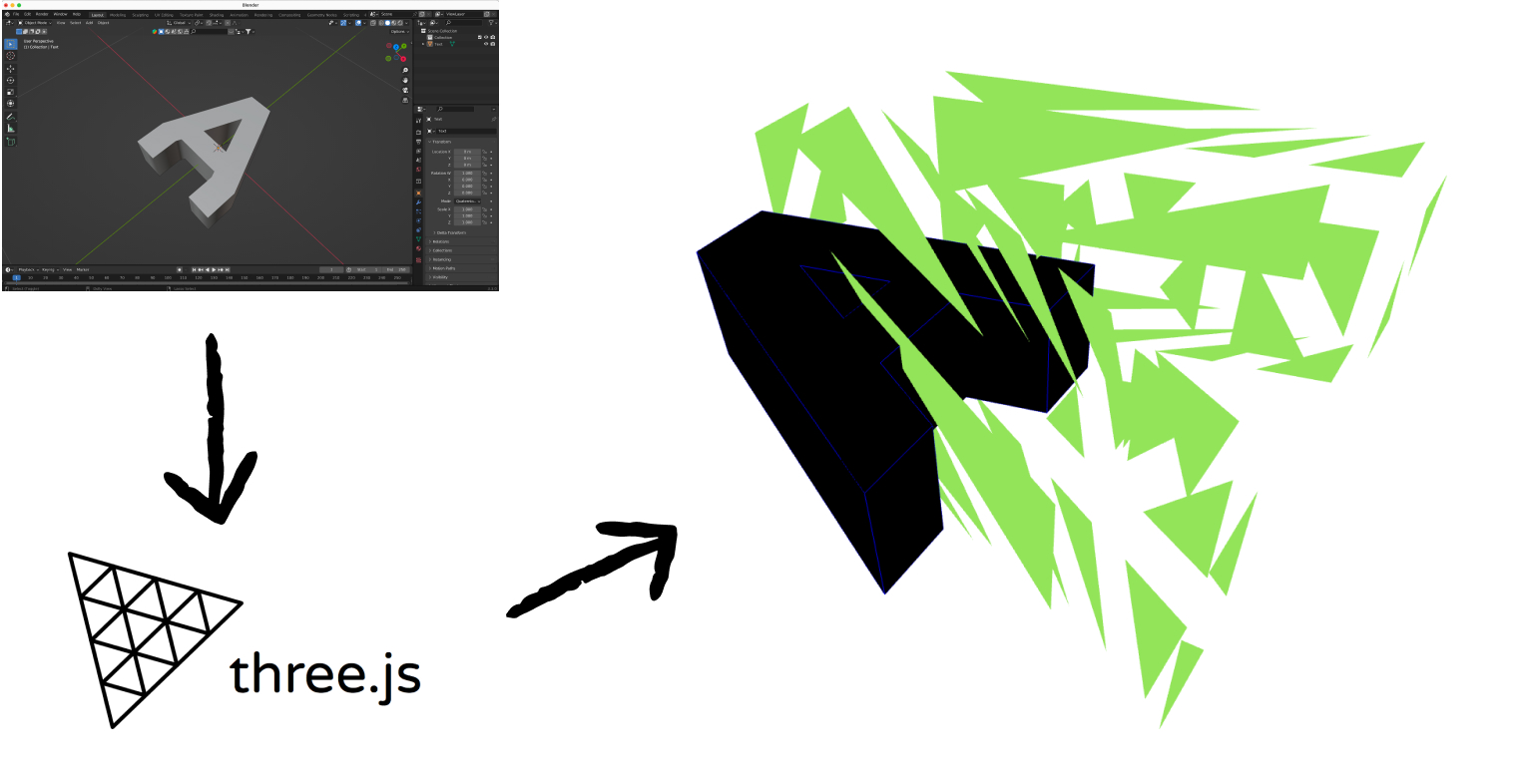

From Mesh to Net: The 3D to 2D Pipeline

To support the iterative making flow shown in the previous scenario, TypoFold translates code-generated 3D forms into foldable paper nets through a structured 3D-to-2D pipeline.

Perceptual Faces vs. Rendering Geometry

While triangulation is efficient for rendering, it became a critical obstacle when building TypoFold—fragmenting perceived surfaces and preventing reliable generation of foldable nets for physical assembly.

Problem

Perceptual Surfaces Were Fragmented by Triangulation

When TypoFold imports 3D letterforms, each surface is automatically triangulated for rendering.While efficient computationally, this breaks a single perceived surface into many small faces—making it difficult to generate paper nets that align with how users cut, fold, and assemble physical forms.

Solution

To address this, I grouped adjacent triangles that (1) share edges and (2) have aligned surface normals,allowing the system to reconstruct perceptually meaningful faces.

This enables the unfolding process to operate on surfaces as users perceive them—rather than on low-level geometric primitives.

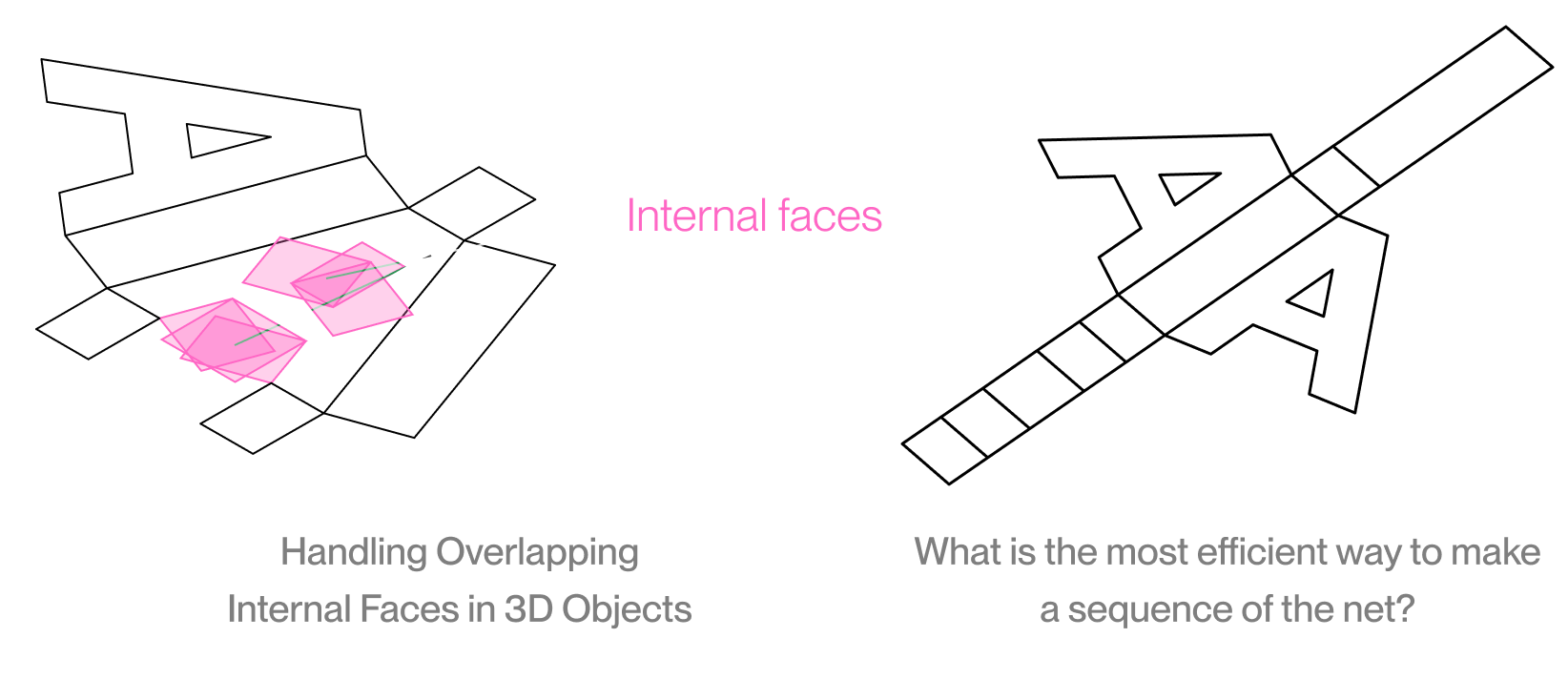

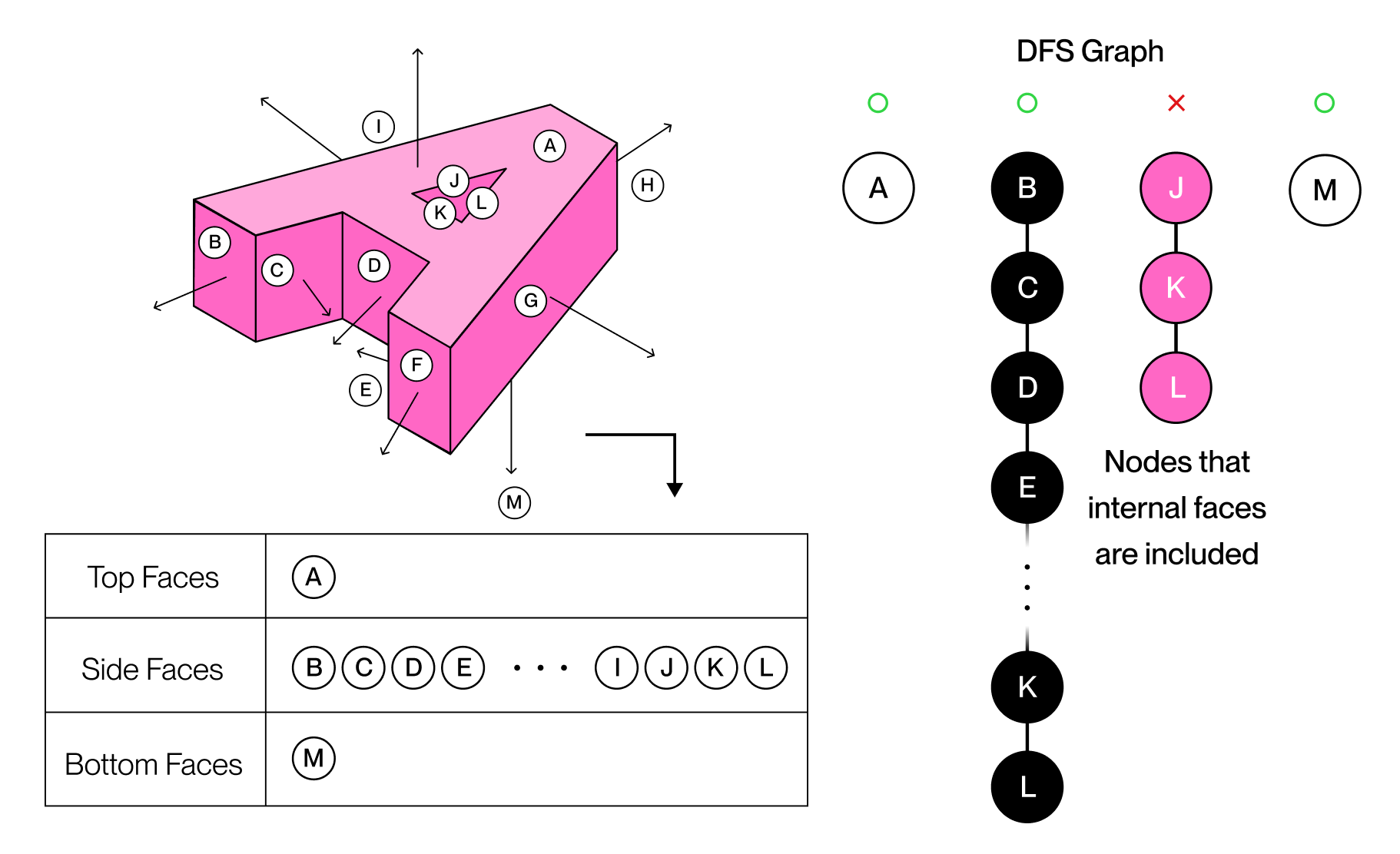

Unfolding breaks due to internal faces

After reconstructing the perceptual faces, another problem came up during net generation. When unfolding them into 2D layouts, internal surfaces were still included, which caused overlaps and made physical assembly impossible. This meant I needed a more selective approach to unfolding.

Problem

Unfolding Internal Faces Breaks Physical Assembly

When unfolding 3D letterforms into paper nets, including all faces caused internal surfaces to overlap in the 2D layout. These internal faces do not contribute to physical assembly and instead produce nets that cannot be cut, folded, or assembled correctly.

Solution

To solve this, I sorted the faces by their orientation and used a DFS algorithm that skips internal faces. This ensures the generated paper nets don't overlap and can actually be assembled by hand.

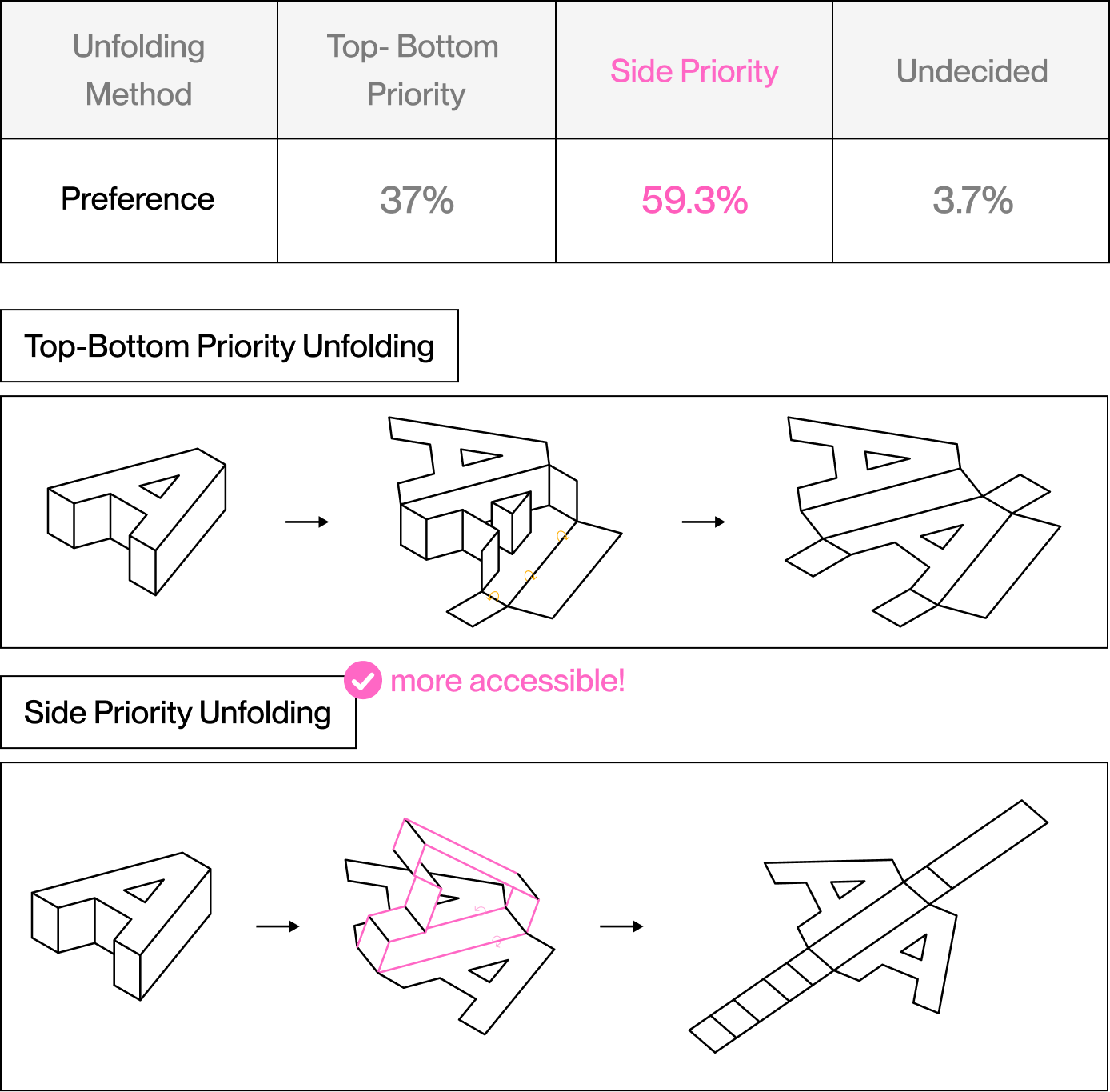

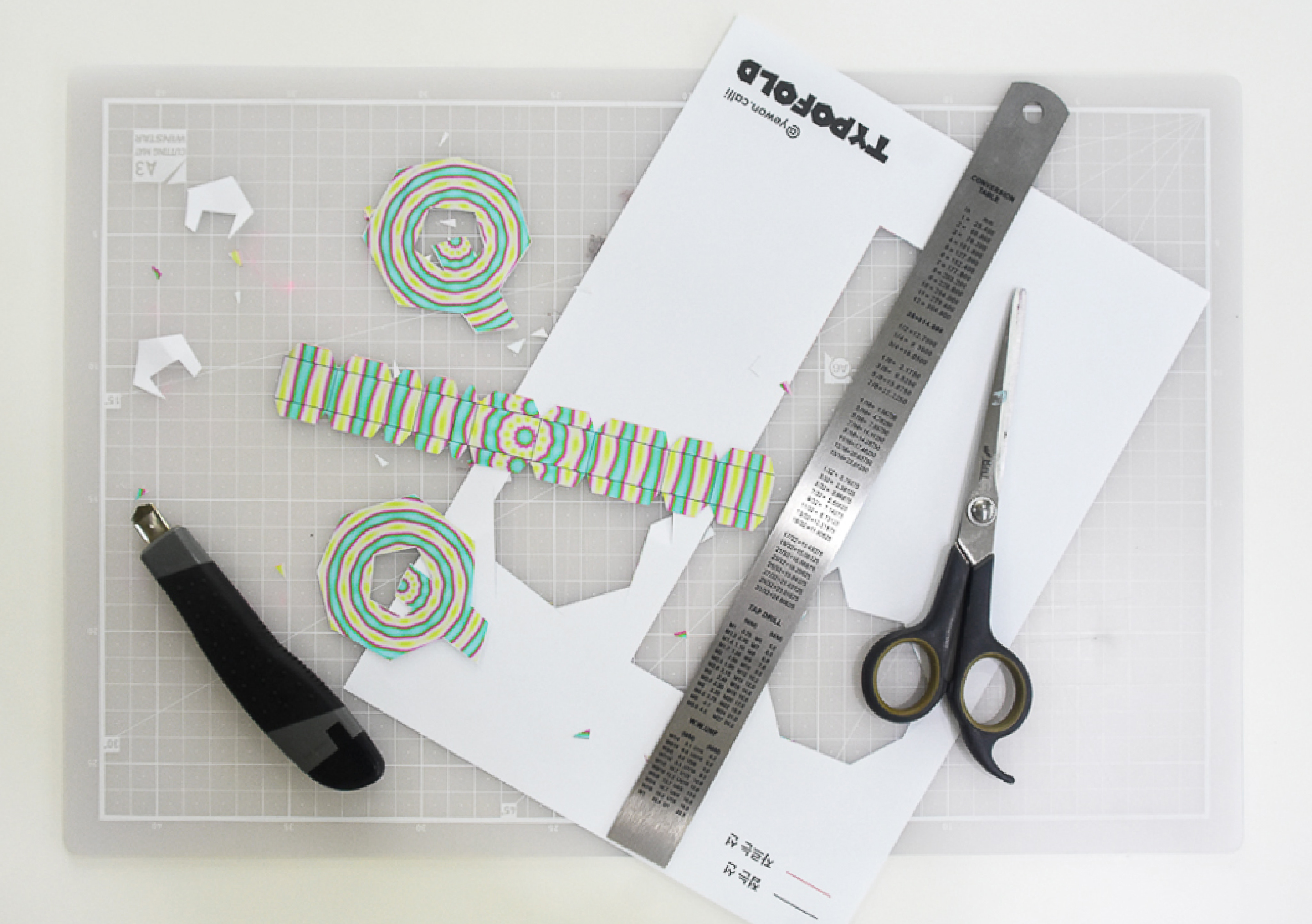

Finding a paper craft template method suitable for actual assembly

After solving structural issues in template generation, I examined how the cutting and folding process differs depending on the unfolding method. I conducted a user preference test to determine which method is most suitable for assembly.

Key Question

"Which unfolding method is easiest to cut, fold, and assemble?"

Participants preferred the side-priority unfolding method and responded that it was easier to cut and assemble. Based on these results, TypoFold adopted side-priority unfolding as the default method.

User Test

User Preference Survey by Unfolding Method

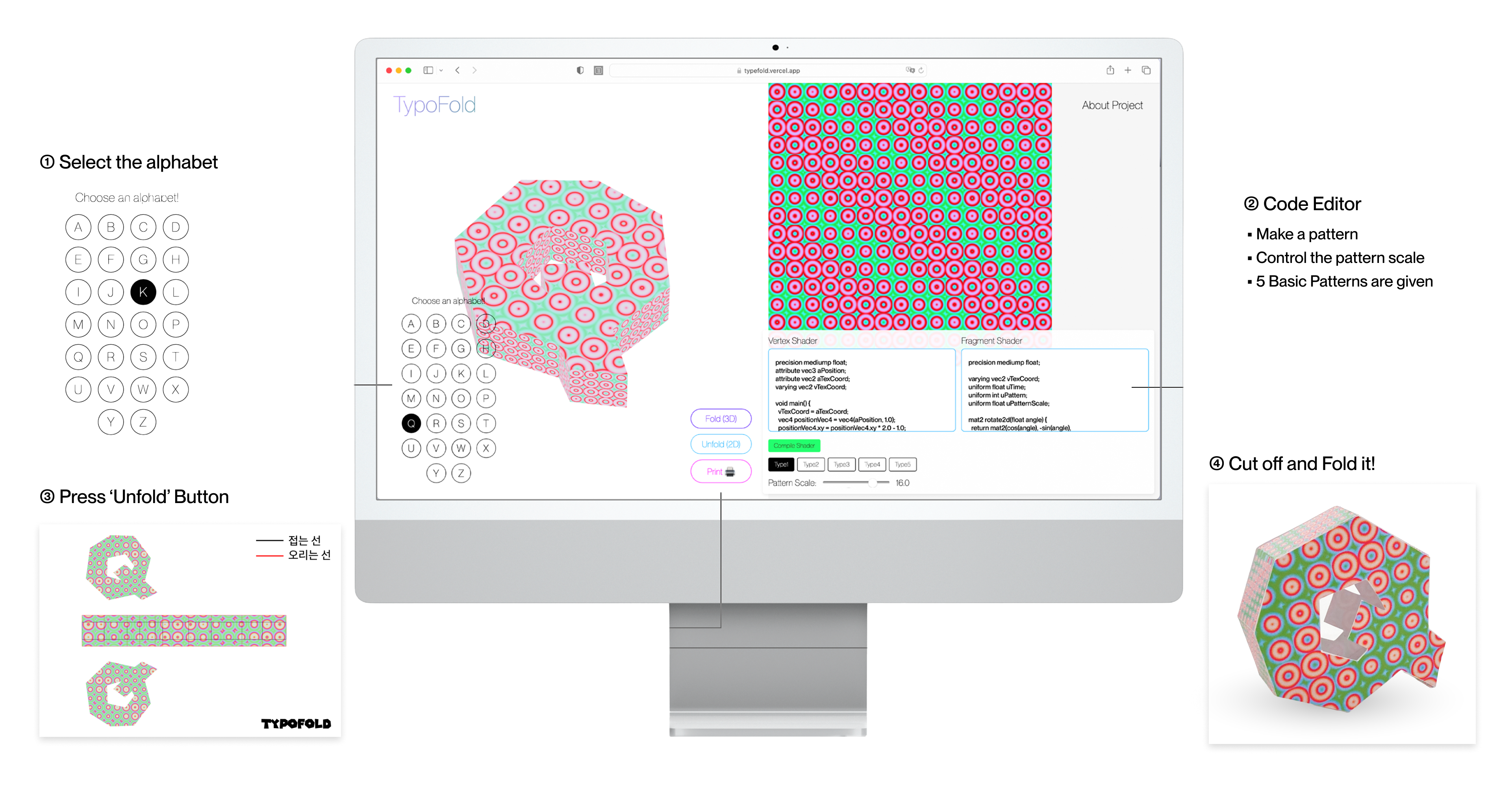

TypoFold, a design tool that converts 3D models into paper crafts

The final web interface of TypoFold, showcasing its core features and user flow.

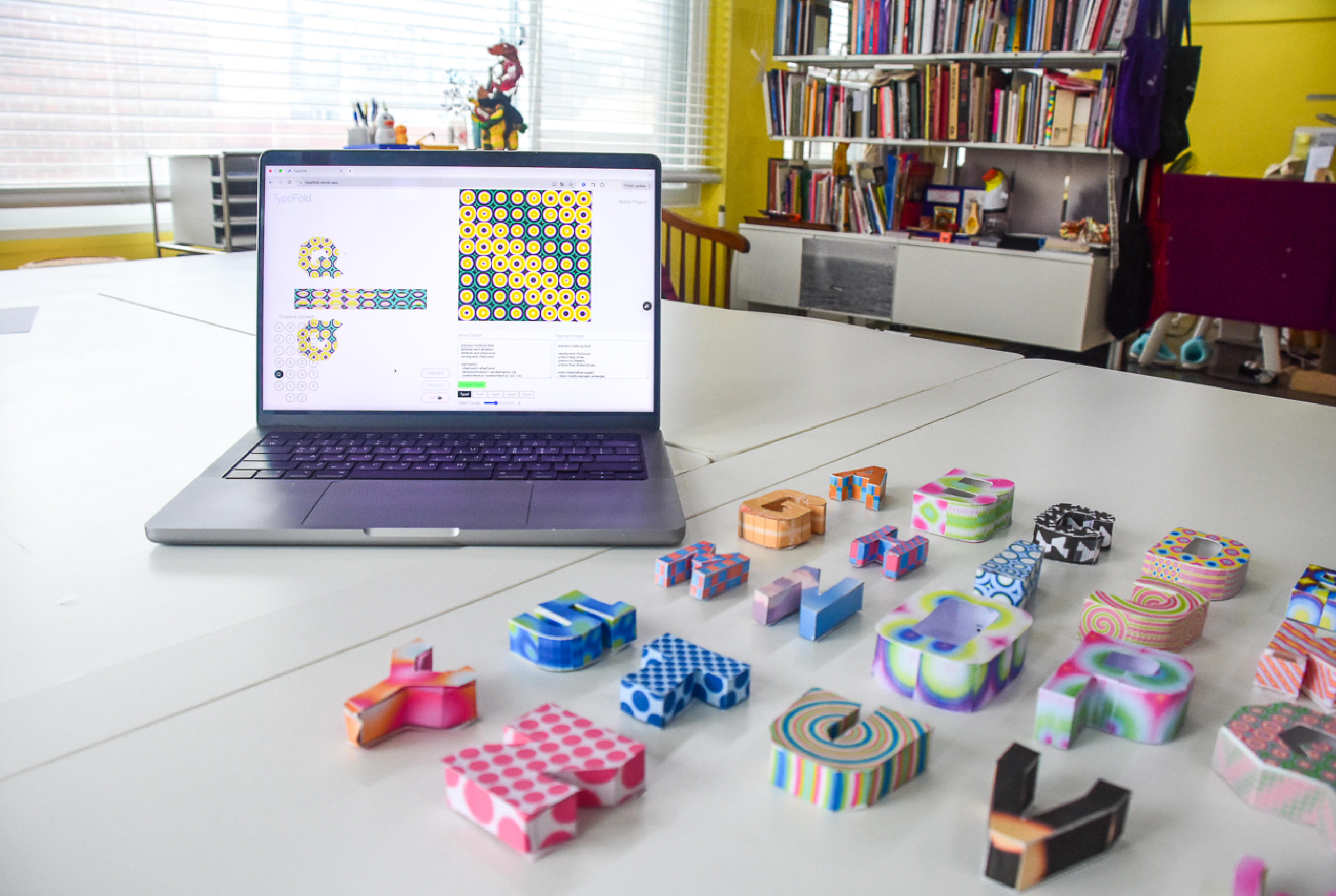

Examples of paper craft outputs created by generating, printing, cutting, folding, and assembling 3D letterforms from A to Z using TypoFold.

Cutting and folding by hand creates attachment to the result

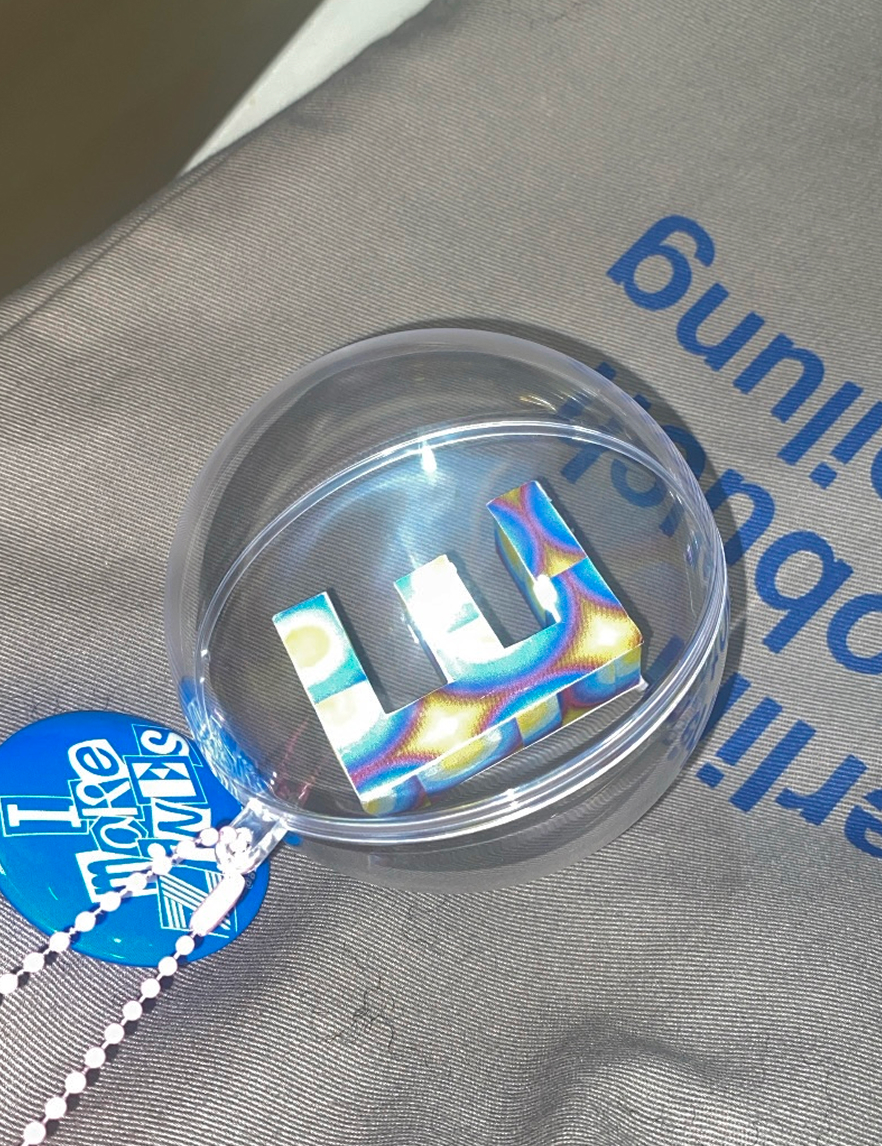

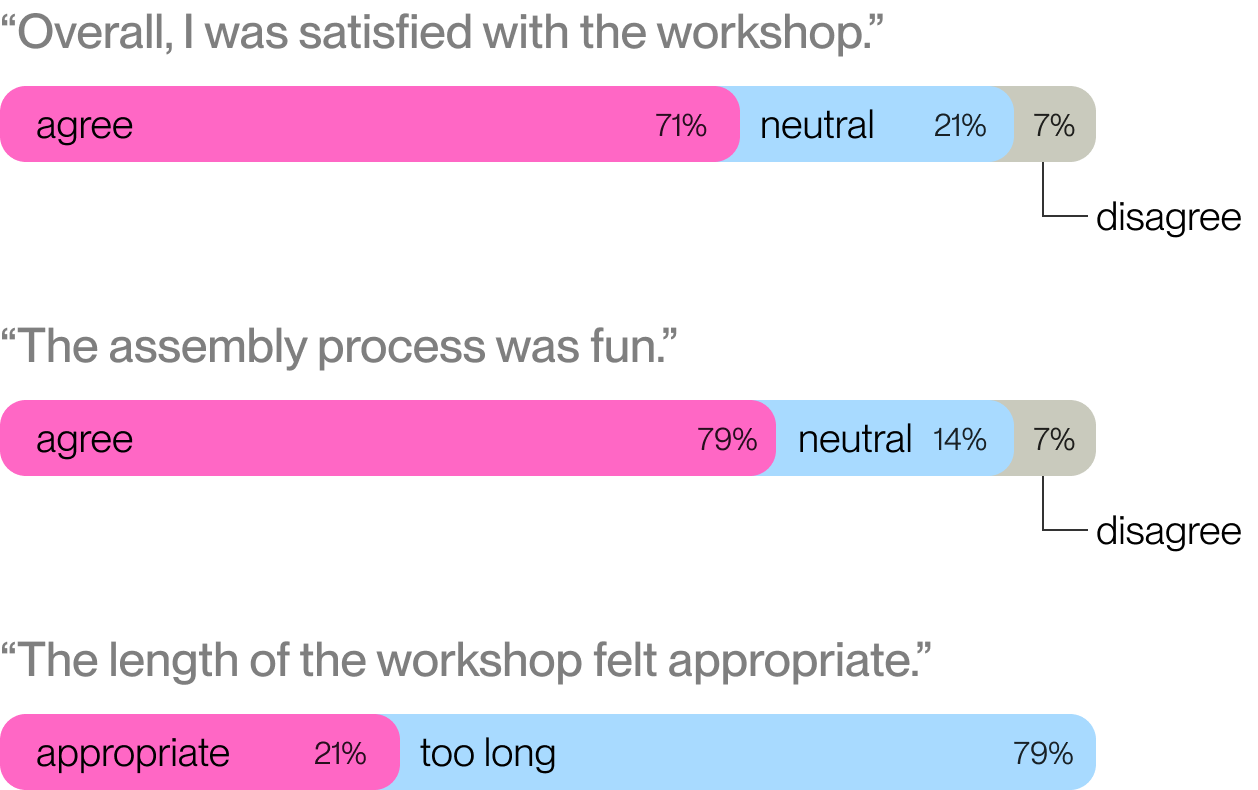

TypoFold met users through the HCI Korea 2025 workshop. Participants learned simple p5.js syntax to create their own patterns, selected their desired alphabet, and made keychains.

Ownership Emerges Through Making

Through a subsequent survey, I confirmed that the process of assembling by hand increased both enjoyment and sense of ownership.

*18 participants responded to the post-workshop survey

In the next phase, I extended TypoFold beyond letterforms to test how the unfolding pipeline performs across more complex 3D geometries.

By applying the system to varied shapes with different topology and surface structures, I evaluated whether the workflow could generalize beyond typography while maintaining physical assemblability and visual coherence.

This shift turns TypoFold from a typography-focused prototype into a broader method for converting digital 3D models into foldable physical structures. At the same time, it revealed new challenges around face segmentation, overlap handling, and maintaining consistency at scale.